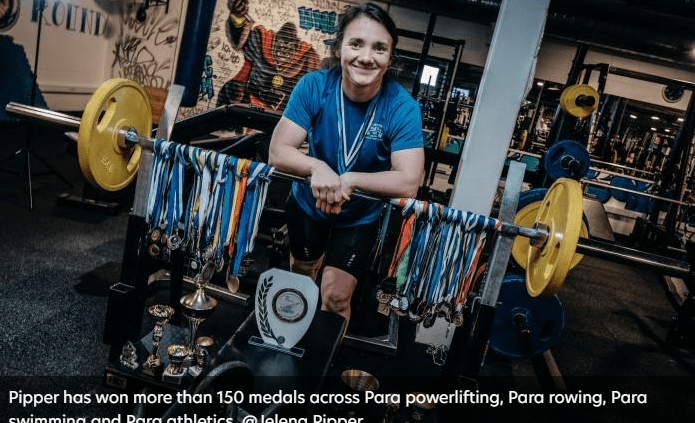

Mother-daughter Para powerlifting duo show strength of women to rise above challenges

Jelena Pipper and her mother Nelli Rjumina are the faces of Estonian Para powerlifting and the main forces driving the sport forward for women in the Baltic states

Estonian Para powerlifter Jelena Pipper does not approach international competitions lightly, having an opportunity to travel to only one or two per year. So when the coach who was assigned to accompany her to the Dubai 2021 World Cup changed his mind three days before the flight, she knew there was only one person who could replace him – her mother.

Nelli Rjumina stepped up to the task without hesitation.

While Rjumina is a cook by profession and has no coaching experience, the mother-daughter duo proved to be the perfect team, keeping each other smiling and breaking national records in the process.

Now they are also working together to help more women experience the joy that sports can bring.

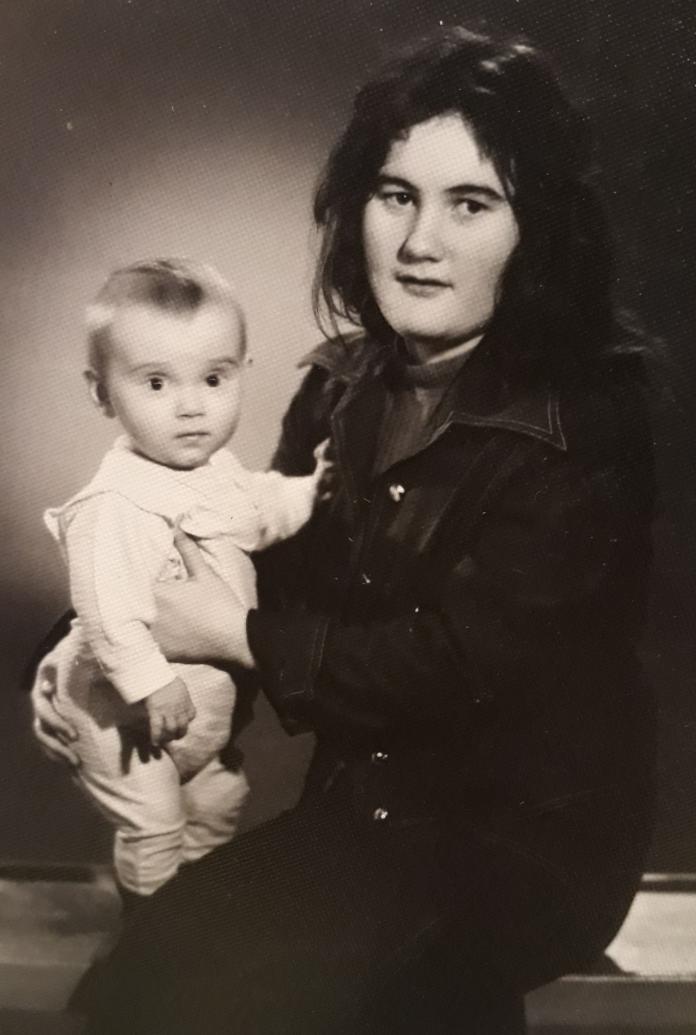

Childhood snapshots

If you are looking for the Estonian Para powerlifting team, you will find all of them in Jelena Pipper’s family photo album.

Rjumina was the one who first introduced her daughter to sports. Born with cerebral palsy, Pipper started with sessions in the pool, which had a calming effect on her nervous system, and later also took up rowing and athletics.

“My mother has been doing aqua aerobics and gymnastics for more than 25 years. She was a motivator and inspiration in all my sporting endeavors,” Pipper said. “In addition to my swimming and rowing training in the past, I was always going hiking and fishing with my mom. We tested new pools together and various lymphatic massages and exercises.

Nelli Rjumina was the first to introduce her daughter to sports. @Jelena Pipper

“Now we cycle together a lot. I am on my tricycle and my mom on a regular two-wheeler. My mom always looked after my health and set an example for me to be healthy. Since she is trained as a chef, she also taught me many useful recipes. Sport has always been in our family life.”

When her mixed coxed four rowing crew fell apart, Pipper looked for other sports to try, and that is when she discovered Para powerlifting.

The best coach

Pipper is currently the only competitive female Para powerlifter not only in Estonia, but in the Baltic region. The three Para powerlifters who represented Estonia before were all male.

Taking up the sport in 2017, Pipper trained alone for a year until she found a male coach to help her. After he left Estonia, she got a new coach that she now trains with four times per week after her full-time job.

Over the past six years Pipper has competed at two World Championships, several regional competitions and World Cups. Most recently, at the 2022 European Open Championships, which took place in Tbilisi, Georgia in September 2023, she finished with a personal best and national record of 62kg in the women’s up to 73kg class.

“I’m getting better. My strength, my muscles are growing year by year, and I am gaining more experience. Experience is crucial because in our country and in the neighbouring countries, there are no such competitions nor athletes, not in Latvia, Lithuania nor Finland. Only men,” Pipper said.

“In 2018 I had my first competition, the European Open Championships in Berck-Sur-Mer, France, and there I finished eighth and my best was 40kg. This was my first competition and I lifted 40kg, and now I lifted 62kg. Look how much I’ve improved!”

While Pipper has a personal coach when she is in Tallinn, but he is not able to travel to competitions. As a result, she has had to travel alone twice, and found both of these experiences emotionally draining.

“She went to Manchester (2021 World Cup) alone. She got there and called me in tears, ‘Why? What am I doing here at all, alone?’,” Rjumina said.

“When she had to go to Dubai (2021 World Cup), our Paralympic Committee assigned her a coach. She did not know him. He did not know her. And three days before the trip he refused to go. He had some other plans for the summer, apparently. She asked me, ‘Mom, can you go?’ and I replied, ‘Of course! Would I ever abandon my child, even if she is an adult, in her 40s? Of course, I will go’.”

And so Rjumina stepped in – surpassing all expectations.

She is accredited as Pipper’s coach, so she comes out on the field of play and helps strap her daughter to the bench. Her presence also has a calming effect.

“When I’m with my mom, my nervous system is in a relaxed state, while I am usually tense due to my condition,” Pipper said. “I feel that the internal spastic tremor in my legs, the whole lower body, decreases and when I hold her hand, even my posture and walk always improve.

“Because my mother is with me when I travel, because we stay in the same hotel, we fly on the same plane and we are together in the warm-up area during the competition, we instantly understand each other and the help I need is always close at hand.

“My mom helps me in the warm-up area by setting the weight and stretching at the end of the workout, because this is the hardest part,” Pipper added. “This is when my body is full of tension. I don’t know how to massage my legs and back, while my mom, who has known me since birth and has always massaged my whole body, especially my legs, since I was born, she can do it.”

Rjumina has now accompanied her daughter to three competitions: the 2021 World Cup in Dubai, UAE, the Parapan American Open Championships in St. Louis, USA in July 2022, and the 2022 European Open Championships in Tbilisi, Georgia.

While Pipper says her mother’s presence at these competitions was irreplaceable, Rjumina herself is humble about her contribution. Instead, it is her daughter she praises most.

“She is a very strong person. She achieved a lot,” Rjumina said. “She started way back in the Soviet times when there was nothing at all. Then there was the period when we became an independent country, and these were very hard times as well and through it all she accomplished everything herself.

“She got an academic degree, which has always been hard for people with disabilities. She learned to drive a car five years ago, because she had to go back and forth. She is like a big official in Estonia, and she still finds time to do (sports). I am proud.”

Making women stronger

This year Pipper is channeling her strength and determination into qualifying for the Paris 2024 Paralympic Games, which would be her first. To accomplish this, she needs to increase her ranking by taking part in more international competitions.

The Estonian Paralympic Committee allocates a small sum to Pipper each year, usually enough to cover one competition trip. The rest – including the costs of Rjumina’s tickets – comes out of the family budget.

The trip to the World Cup in St. Louis, for example, Pipper financed with the support of her partner. Her mother, who paid for the trip with her pension savings, and 17-year-old son Sebastian Sepp also made the journey.

A media studies student, Sepp films videos of his mother at Para powerlifting competitions so she can later use them to promote the sport in Estonia. Pipper has already gone on numerous television and radio programmes where she speaks passionately about getting more women to take up Para sports.

She amplifies this message through her official position in various women’s organisations. She is the chairman of the board of the Tallinn and Harju County Union of Disabled Women and founding member and member of the board of the Estonian Association of Disabled Women.

“Women with special needs should practise sports because this improves their physical and mental health. Their circle of friends and their horizons expand. Their self-esteem grows because the body feels good,” Pipper said.

“This sport affects a person’s whole physical state. For example, my left arm is weaker, but it became stronger now. Before I used to slouch more, and now if I am not nervous, I can sit up straight and I will be comfortable sitting up straight. Can you believe it? A person is all twisted up, with spasms, but when they train in the gym and do exercises for the chest, the back, their posture improves and their gait improves.”

While Pipper and Rjumina’s message is that any woman can be as strong as the strongest Para powerlifter, they also want women to know that shedding a few tears is perfectly fine too – especially if you are watching your daughter bench press her personal best.

“I was crying now,” Rjumina said after watching Pipper lift 10kg under her bodyweight in Tbilisi. “I think it is my nerves just letting go. She turns to me, ‘Mom, why do you cry every time?’ and I say, ‘I can’t help it! My nerves are shot (from watching) and I can’t control them’.”